On June 27, 2022, the Supreme Court of the United States issued its opinion in the companion cases Ruan v. United States and Kahn v. United States. The Court, with Justice Breyer authoring the opinion, addressed a circuit split regarding the mens rea requirement for a conviction under § 841 of the Controlled Substances Act (CSA). The Court ruled 9-0 (Alito, Barrett, and Thomas concurring) that, for the crime of prescribing controlled substances outside the usual course of professional practice in violation of 21 U.S.C. § 841, the mens rea “knowingly or intentionally” applies to the statute’s “except as authorized” clause.

This ruling is significant for a number of reasons. Mainly, the decision disposes of the “objective reasonableness” test and conduct-based standards which were used in many circuits when physicians were charged criminally for “over-prescribing.” Under these previous standards, prescribing cases often turned on expert testimony put on by the government in which physicians testified that the defendant’s prescribing was so outside the course of professional practice that it crossed into criminal behavior. In circuits where the objective reasonableness test and conduct-based standards were the law, a prescriber’s argument that he or she was acting in good faith and prescribing for a legitimate medical purpose was generally not a viable defense if his or her actions could not be considered “objectively reasonable.”

The new ruling adopts a stricter standard for the government. Now, when the government brings a criminal CSA case against a physician, the prosecution must prove, either by direct or constructive evidence, that the defendant physician knew and intended to prescribe drugs in an unauthorized manner.

The Law at Issue and the Circuit Split

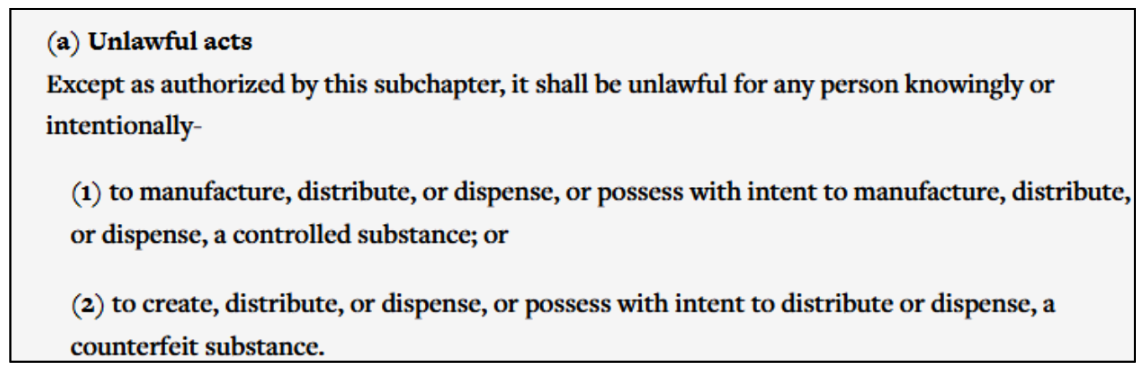

This case involved the scienter requirement for 21 U.S.C. § 841, which reads in relevant part:

Under the Supreme Court’s prior decision in United States v. Moore, 423 U.S. 122 (1975), “registered physicians can be prosecuted under [the CSA] when their activities fall outside the usual course of professional practice.” Lower courts largely agreed on the basic elements needed to support a conviction of a practitioner’s violation of § 841. The United States had to prove that a defendant (1) knowingly and intentionally, (2) distributed or dispensed a controlled substance, (3) not for a legitimate medical purpose and outside of the usual course of professional medical practice. The disagreement between the circuits revolved around what was needed to show that the unauthorized prescribing or distribution at issue was knowing and intentional, and the utilization of an objective reasonableness and/or good faith standard.

Although the nuances and case law varied amongst the circuits, there were three general baskets into which the scienter standards could be organized:

Conduct-Based Standard (10th, 11th, 5th): This was the approach utilized by the lower court in which the Ruan and Khan case originated, the 11th, as well as in the 10th and 5th circuits. This approach substantially abandoned any scienter requirement, and effectively allowed the United States to convict a practitioner via strict liability by centering the inquiry on scienter on whether, from an objective standpoint, the drugs were dispensed in the usual course of professional practice.

Objective Good Faith Standard (2nd, 4th, 6th, 8th): Under the objective good faith standard, a practitioner did not violate the CSA if he or she reasonably believed that his or her actions were for a legitimate medical purpose within the usual course of professional medical practice. This approach was less harsh than the conduct-based standard, as a practitioner’s objectively reasonable belief that his or her actions were legitimate and reasonable was sufficient to avoid criminal liability. The 4th Circuit, which encompasses Virginia, followed the objective good faith standard.

However, the fact that the standard required the defendant’s belief to be “objectively reasonable” still allowed the government to obtain a conviction by presenting expert testimony that the defendant’s actions were so outside the usual course of professional practice that they could not have been considered as “objectively reasonable.”

Subjective Good Faith Standard (1st, 7th, 9th): Under the subjective good faith approach, a practitioner did not violate the CSA if he or she possessed a sincere, subjective belief that he or she prescribed the controlled substance for a legitimate medical purpose in the usual course of his or her professional medical practice. Under this standard, even an objectively unreasonable belief is sufficient to show good faith as long as it is held sincerely. This is the standard the Supreme Court ultimately adopted in Ruan/Khan.

Holding and Implications

In the Ruan/Khan opinion, the Supreme Court held that “once a defendant meets the burden of producing evidence that his or her conduct was ‘authorized,’ the government must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that a defendant knowingly or intentionally acted in an unauthorized manner.” The Court noted that the legal authorization to prescribe a controlled substance “plays a ‘crucial’ role in separating innocent conduct — and, in the case of doctors, socially beneficial conduct — from wrongful conduct.” A “strong scienter requirement helps to diminish the risk of ‘overdeterrence,’ i.e., punishing acceptable and beneficial conduct that lies close to, but on the permissible side of, the criminal line.” The Court additionally emphasized that the potential for decades of incarceration and severe fines violations of 21 U.S.C. § 841 militated for a stringent scienter requirement.

In the Court’s opinion, Justice Breyer explicitly rejected the government’s contention that 21 U.S.C. § 841 should be read as requiring an "objectively reasonable good-faith effort" by the prescriber in order to avoid criminal liability. He noted that such an interpretation would effectively place the burden on a defendant to prove that his or her mental state is that of a "hypothetical 'reasonable' doctor." The government additionally contended that utilizing a subjective reasonableness standard would allow “bad-apple(s)” to hide behind an unreasonable and fictitious interpretation of what and how they were authorized to prescribe by simply stating that they sincerely believed that their actions were authorized and acceptable. The Court expressly rejected this line of argument, emphasizing that such an argument could be applied to almost any criminal case. The Court additionally noted that the government could prove the scienter requirement by circumstantial evidence.

Ultimately, the holding in Ruan and Khan simplifies the scienter requirement for violations of 21 U.S.C. § 841. In the Fourth Circuit, it replaces the objective reasonableness good faith standard, which involved determining what a reasonable belief was as to a legitimate medical purpose and the usual course of professional medical practice, with a basic credibility determination. The s decision shifts the burden of proving mens rea away from the defendant, who, in the Fourth Circuit, was effectively required to prove a lack of guilty mental state via quasi-affirmative defense. It places that burden back on the government, where it rests when prosecuting almost any other criminal offense. If a practitioner shows that he or she is authorized to prescribe the controlled substance at issue, a jury or judge can only appropriately find him or her guilty of violating § 841 if the government proves beyond a reasonable doubt that he or she knew that the prescription or distribution was illegal, and that such unauthorized prescription or distribution was intentional. The actions of a hypothetical reasonable practitioner is no longer dispositive. As with most criminal cases focusing on scienter, the inquiry has shifted to a determination of whether the jury believes the defendant, or the government.

The Ruan/Khan decision should provide some comfort for prescribers of opioids, benzodiazepines, and other DEA-scheduled substances. This decision means that the government cannot prove a violation of 21 U.S.C. § 841 based on a deviation from the expected behavior of an imaginary “reasonable” physician. The Court effectively affirmed that intent is an element of the crime, and not an affirmative defense the defendant must prove. Now, the government has to prove the mental state beyond a reasonable doubt, just like it would for any other criminal case.

However, prescribers should keep in mind that the Supreme Court’s opinion does not absolve them from their duty to prescribe in a responsible manner and only in the context of a bona fide practitioner-patient relationship. While the evidentiary standard may now be higher, criminal sanctions are still available for illegal prescribing, and prosecutors will not be deterred from prosecuting cases with egregious facts. Furthermore, the Ruan/Khan decision will not shield providers in civil actions, nor does it have any bearing on regulatory agencies, such as the Virginia Board of Medicine. Prescribers are still required to follow the Board’s Regulations Governing Prescribing of Opioids and Buprenorphine (18 VAC 85-21-10 et seq), and violations of these regulations still very well may result in disciplinary action.